(Part 4 of the Food Sensitivity series)

Did you ever lay down at night and notice a new runny congested nose, itching, scratchy throat, or vague gastrointestinal (GI) discomfort? Maybe it was something you ate—food and drink containing histamines. For some people, especially foodies, edible sources of histamines add up to cause these and other symptoms.

So, what is histamine? It is a chemical, a biogenic amine, made by mast cells that are distributed throughout your body’s tissues and by blood cells called basophils. It mediates immune responses to allergens and infection and has neurologic functions in the brain (wakefulness and temperature regulation) and GI tract (stimulates stomach acid). Beyond what your body makes, some foods you eat may provide more.

High protein foods naturally contain biogenic amines including histamine, but these can also be found in some plant products. Histamine is also created by bacteria, yeasts, and molds in foods that have been fermented, cultured, aged, poorly refrigerated, or left on the counter too long. Ingested histamines have local stomach and intestinal effects and are also absorbed to affect the body at large.

While allergies are what most people associate with histamines, non-allergic histamine reactions also occur, usually within a few hours of consuming histamine-containing foods. Histamines affect the skin, respiratory passages, cardiovascular tissues, or GI tract and symptoms are like those for an allergic response (watery, itchy eyes and nose, sneezing, nasal and chest congestion, wheezing, palpitations, itchy skin, rash, hives, or GI symptoms such as cramping, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, or bloating). The nervous system can also be affected, with headaches and perhaps, difficulty falling asleep.

So, who experiences non-allergic histamine responses? Someone who overwhelms their body with consumed histamines. For example, a charcuterie platter of aged and hard cheeses and dry-fermented meats washed down with red wine or a craft brew is a classic combination to incite symptoms. Responses can range from barely noticeable to severe and individual sensitivity thresholds vary widely.

Most commonly, mild non-allergic histamine reactions occur intermittently. Curiously, the same person might manifest a runny nose and congestion in one instance and generalized itching in another. Others might show signs in a specific area of the body and exhibit just one or two prominent symptoms like headache or acid reflux with cough or postnasal drip with annoying throat clearing or crampy GI pain. These inconsistent patterns and presentations of symptoms make histamine sensitivity difficult to sort out.

To add to the complexity, histamine responses appear to be influenced by estrogen fluctuations during menstrual cycles or with perimenopause. Elevated histamine levels may contribute to increased menstrual cramps.[1]

Elevated histamine levels can incite headaches. Unfortunately, histamine’s influences on headaches (“sinus” or migraine) are not well studied, especially regarding whether a histamine-restricted diet would help reduce their incidence.

How do histamine levels get to be elevated? Three mechanisms are involved. 1) Specific foods directly contribute to the histamine load. 2) Other foods cause special cells in the gut lining to release histamine. 3) If the enzyme that breaks down histamine, diamine oxidase (DAO) is deficient or ineffective, histamine levels build up.[2]

DAO activity is especially prominent within the intestinal tract, the kidneys, and placentas in pregnant women. (High placental levels of DAO may explain reduced food sensitivity in pregnant women.[3]) DAO insufficiency can be hereditary, age-related, or due to competition from medications or foods containing other biogenic amines. Estrogen also influences DAO functioning.

Most people do fine when eating their regular diet; however, special holiday foods, drinking fermented beverages like beer or wine with a meal, or starting certain medications might tip the scales toward developing histaminic symptoms. Dining out can be problematic if menu items contain large amounts of histamine-containing foods.

I suspect most people attribute vague histamine-related symptoms to other causes, but severe problems bring patients to the doctor. Chronic hives, unpredictable diarrhea, recurrent abdominal pain, and sporadic low blood pressure with dizziness and fainting are serious complaints and should be evaluated by your physician.

If no food allergies or other causes are found and significant histamine-related symptoms continue, Histamine Intolerance might be suspected.[4] A recently described diagnosis, histamine intolerance affects an estimated 1% of the population. Of these patients, 80% are middle-aged and likely to be female.[5] Indeed, this timing correlates with perimenopause with its fluctuating levels of estrogen which impact histamine sensitivity.

Keeping a food diary with any attendant symptoms is important to evaluate histamine sensitivity. Those with moderate-to-severe sensitivity will benefit from a referral to a dietician/nutritionist for guidance on an elimination diet and, alternatively, what can be eaten. Persons with milder symptoms or intermittent histamine sensitivity may do OK with some minor adjustments. Here are some recommendations:

** Don’t defrost foods on the counter.

** Put mealtime foods in the fridge as soon after eating as possible.

** Eat fresh meats or fish right away or freeze them after purchase.

** Fish that is frozen at sea (FAS) is safest.

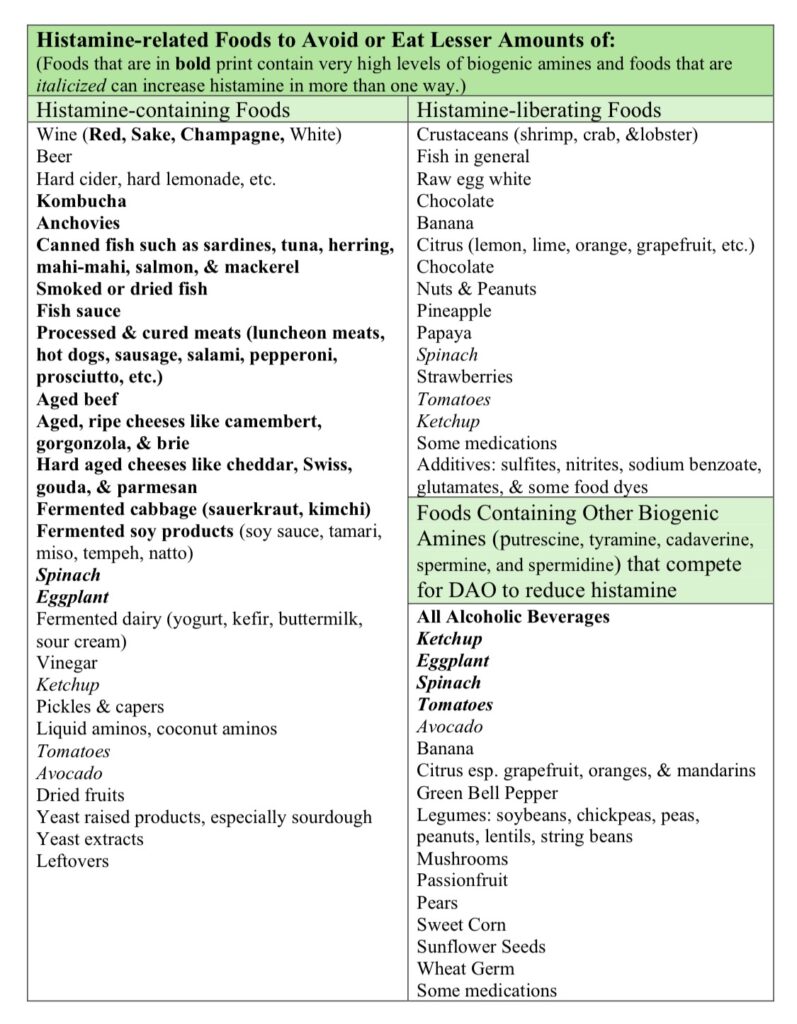

** Eliminate foods highest in histamines (and other biogenic amines) from your diet: dry-aged sausages, cured meats, aged cheeses, canned fish, eggplant, spinach, fermented soy products, beer, wine, and sauerkraut/kimchi.

** Eat smaller amounts of histamine-releasing foods: citrus, tomatoes, bananas. See table below.

** Avoid combinations of histamine-containing and -releasing foods in cooking.

** Reduce or omit ingredients used to ramp up “umami” in dishes—anchovies, parmesan rinds, miso, and liquid aminos.

** Read labels and avoid food additives like sulfites, sodium benzoate, nitrites, glutamates, and some coloring agents since they can stimulate mast cells to release histamine.[6]

** How you cook affects histamine levels. Histamine is not removed by heating; however, boiling and draining off the cooking water leads to reductions in histamine levels, especially spinach. Grilling fish and meats can increase histamine content. Even fried vegetables contain more histamines compared to boiled or raw.[7]

** Eat a well-rounded diet to provide vitamin C, B6, and copper to support the synthesis of DAO.

** Taking diamine oxidase supplements (from pork or beef kidneys or plant-derived) with a meal may help, but there are currently no standards for this supplement and some without enteric-coatings may be degraded by stomach acid. Limited studies (using small numbers of subjects) have shown some improvement of histamine reactions, including headache.[8]

** Could antihistamines help? On occasion, although most doctors would not recommend them except for short term or intermittent use. Non-drowsy formula second generation antihistamines for seasonal allergies like loratadine, cetirizine, and fexofenadine might help for generalized symptoms, but they are not without their own side effects. H2 acid-blocking agents taken on an as needed basis might also help.

References for Table of Histamine-containing foods[9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15]

[1] Laura Maintz and Natalija Novak, “Histamine and Histamine Intolerance,” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 85, no. 5 (May 1, 2007): 1185–96, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/85.5.1185.

[2] Oriol Comas-Basté et al., “Histamine Intolerance: The Current State of the Art,” Biomolecules 10, no. 8 (August 14, 2020): E1181, https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10081181.

[3] Maintz and Novak, “Histamine and Histamine Intolerance.”

[4] Wolfgang J. Schnedl et al., “Evaluation of Symptoms and Symptom Combinations in Histamine Intolerance,” Intestinal Research 17, no. 3 (July 2019): 427–33, https://doi.org/10.5217/ir.2018.00152.

[5] Maintz and Novak, “Histamine and Histamine Intolerance.”

[6] Martin Hrubisko et al., “Histamine Intolerance—The More We Know the Less We Know. A Review,” Nutrients 13, no. 7 (June 29, 2021): 2228, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072228.

[7] Bo Young Chung et al., “Effect of Different Cooking Methods on Histamine Levels in Selected Foods,” Annals of Dermatology 29, no. 6 (December 2017): 706–14, https://doi.org/10.5021/ad.2017.29.6.706.

[8] Hrubisko et al., “Histamine Intolerance—The More We Know the Less We Know. A Review.”

[9] Comas-Basté et al., “Histamine Intolerance.”

[10] Matteo Briguglio et al., “Dietary Neurotransmitters: A Narrative Review on Current Knowledge,” Nutrients 10, no. 5 (May 13, 2018), https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10050591.

[11] Sònia Sánchez-Pérez et al., “Biogenic Amines in Plant-Origin Foods: Are They Frequently Underestimated in Low-Histamine Diets?,” Foods 7, no. 12 (December 14, 2018): 205, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods7120205.

[12] Charlie Li, Gordon Vrdoljak, and B. Moezzi, “Sampling and Analysis of Histamine in Fish Products from Local Northern California Markets,” 2018, https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-7091.100089.

[13] Maintz and Novak, “Histamine and Histamine Intolerance.”

[14] Marta Moniente et al., “Histamine Accumulation in Dairy Products: Microbial Causes, Techniques for the Detection of Histamine-Producing Microbiota, and Potential Solutions,” Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 20, no. 2 (2021): 1481–1523, https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12704.

[15] Hrubisko et al., “Histamine Intolerance—The More We Know the Less We Know. A Review.”

Leave a Reply